Bibliography Background About KRIS

Hypothesis #1: The abundance and distribution of Atlantic salmon in the Sheepscot River basin have been reduced.

There are now seven rivers in the Gulf of Maine, including the Sheepscot River, recognized as having distinct Atlantic salmon gene resources that merit protection under the Endangered Species Act as a Distinct Population Segment (DPS). The historical level of abundance of Atlantic salmon in the Sheepscot River at the time of early European contact is unknown, but the watershed was originally settled by fishermen and trappers and prized for its spring run salmon (Foye, 1967). Although there is no baseline information from written accounts of salmon returns or catches in the Sheepscot River, Baum (1997) used historical records to estimate the run at least 100,000 adults annually in the nearby, but larger, Penobscot River.

There are now seven rivers in the Gulf of Maine, including the Sheepscot River, recognized as having distinct Atlantic salmon gene resources that merit protection under the Endangered Species Act as a Distinct Population Segment (DPS). The historical level of abundance of Atlantic salmon in the Sheepscot River at the time of early European contact is unknown, but the watershed was originally settled by fishermen and trappers and prized for its spring run salmon (Foye, 1967). Although there is no baseline information from written accounts of salmon returns or catches in the Sheepscot River, Baum (1997) used historical records to estimate the run at least 100,000 adults annually in the nearby, but larger, Penobscot River.

Photo: Atlantic salmon caught in the Sheepscot River sometime in the 1960's. From Meister (1983).

Foye (1967) contains the following quote from Chase (1941) describing historic fish abundance:

"In the Sheepscot River before the mills polluted the stream, were great schools of fish. Salmon, shad and alewives were at the falls at Head Tide; striped bass at Sheepscot Falls; smelts were so abundant in this and the neighboring rivers that they were used as fertilizer."

Atlantic salmon populations in New England likely began their decline in the 17th Century, during early periods of white settlement, due to intensive fishing pressure and habitat destruction. For example, commercial fishing for salmon in Maine began as early as 1628, but there were virtually no restrictions on methods of catch or limits until 1867 (Baum, 1997). In the Sheepscot River basin, dams were erected to provide water power for mills beginning in the 1760's (Foye, 1967). At least 44 dams were operated along the Sheepscot River and its tributaries and the lowest at Head Tide blocked Atlantic salmon from virtually the entire Sheepscot River watershed (Maine Dept. of Dam Safety, 1921; Halsted, 2002). Photo: West Branch Sheepscot River and abandoned Sprouls Mill Dam. 1950.

Atlantic salmon populations in New England likely began their decline in the 17th Century, during early periods of white settlement, due to intensive fishing pressure and habitat destruction. For example, commercial fishing for salmon in Maine began as early as 1628, but there were virtually no restrictions on methods of catch or limits until 1867 (Baum, 1997). In the Sheepscot River basin, dams were erected to provide water power for mills beginning in the 1760's (Foye, 1967). At least 44 dams were operated along the Sheepscot River and its tributaries and the lowest at Head Tide blocked Atlantic salmon from virtually the entire Sheepscot River watershed (Maine Dept. of Dam Safety, 1921; Halsted, 2002). Photo: West Branch Sheepscot River and abandoned Sprouls Mill Dam. 1950.

Atkins (1887) described how the dams had caused such a decline in the Sheepscot Atlantic salmon population that net catches in the lower river were only 12-15 adult fish in 1872 and 1873 and none were caught in 1880. Meister (1982) postulated that a remnant Atlantic salmon run had been able to survive in the lower Sheepscot River below the Head Tide Dam by spawning in small tributaries and the mainstem above the tidal salt wedge.

With the advent of inexpensive electricity to power mills and machinery, many dams were abandoned in the 20th Century. The Sprouls Mill Dam on the West Branch Sheepscot River (at left) serves as an example, having been constructed in 1850 as a grist mill, converted to a saw mill and then a shingle mill, which was operated until about 1940. Such dams would block flows overnight to store water that ran the mill the next day. In the 1950's, active dam removal began to open up historic salmon habitat (Baum, 1997), including in the Sheepscot River basin (Bryant and Fletcher, 1951), and Maine Atlantic salmon populations began to rebuild. Most significantly for the Sheepscot, in 1952 Head Tide Dam was modified to allow fish passage (Stickney, 1959).

Meister (1982) stated that restoration of the Sheepscot River Atlantic salmon population with remnant wild fish was not feasible, because the population was too small, and Canadian Atlantic salmon were stocked in the Sheepscot River basin to rebuild runs from 1948-1960. Despite planting of Canadian Atlantic salmon in Gulf of Maine DPS rivers in this period, the National Academy of Sciences (NRC, 2003) found that: "Maine streams have salmon populations that are genetically as divergent from Canadian salmon populations and from each other as would be expected in natural salmon populations anywhere else in the Northern Hemisphere."

Angler Atlantic salmon catch in the Sheepscot River from 1948-1995 (at left) indicates that several dozen were harvested in many years from 1955 to 1984, but after that catches began to decline. From 1995 to 1999, only catch and release fishing was allowed, and since December 1999 all recreational fishing for anadromous Atlantic salmon in Maine has been prohibited (USFWS and NOAA, 2000). The decline in catches are an indication that the adult salmon population also decreased. The data represent reported catches and should be regarded as a minimum and roughly 60-80% of the actual catch (Meister, 1982). Data were contributed by the Maine Atlantic Salmon Commission, Sidney Field Office. Chart from KRIS Sheepscot V 1.0.

Angler Atlantic salmon catch in the Sheepscot River from 1948-1995 (at left) indicates that several dozen were harvested in many years from 1955 to 1984, but after that catches began to decline. From 1995 to 1999, only catch and release fishing was allowed, and since December 1999 all recreational fishing for anadromous Atlantic salmon in Maine has been prohibited (USFWS and NOAA, 2000). The decline in catches are an indication that the adult salmon population also decreased. The data represent reported catches and should be regarded as a minimum and roughly 60-80% of the actual catch (Meister, 1982). Data were contributed by the Maine Atlantic Salmon Commission, Sidney Field Office. Chart from KRIS Sheepscot V 1.0.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Maine Atlantic Salmon Commission operated a weir on the Sheepscot River below Head Tide Dam from 1956-1999 to catch adults (at left) and downstream-migrating smolts. Fifty-five adult salmon were captured in 1957 and 99 were captured in 1959. Due to earlier ice-out dates, traps began operating several weeks earlier in the season in 1957 and 1959 than in 1956 and 1958. Because of this, counts for 1956 and 1958 are incomplete and the actual numbers of fish were likely substantially greater than are shown in these data. Data are from Stickney (1959) and chart is from KRIS Sheepscot V 1.0.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Maine Atlantic Salmon Commission operated a weir on the Sheepscot River below Head Tide Dam from 1956-1999 to catch adults (at left) and downstream-migrating smolts. Fifty-five adult salmon were captured in 1957 and 99 were captured in 1959. Due to earlier ice-out dates, traps began operating several weeks earlier in the season in 1957 and 1959 than in 1956 and 1958. Because of this, counts for 1956 and 1958 are incomplete and the actual numbers of fish were likely substantially greater than are shown in these data. Data are from Stickney (1959) and chart is from KRIS Sheepscot V 1.0.

When the weir at the same location was operated from1994-1996 only 8 to 22 adults salmon were observed each year. Comparing these data to earlier data indicates a substantial decline in numbers of returning adult salmon between the 1956-1959 period and the 1994-1996 period.

Atlantic salmon redd counts in the Sheepscot River from 1984-2003 (at left) show declining trend a similar to angler catch, likely reflecting decreasing adult escapement. Sampling effort was not necessarily the same in all years, and no surveys were conducted in 1985 and 1991. Data from the Maine Atlantic Salmon Commission (ASC). Chart from KRIS Sheepscot V 1.0.

Atlantic salmon redd counts in the Sheepscot River from 1984-2003 (at left) show declining trend a similar to angler catch, likely reflecting decreasing adult escapement. Sampling effort was not necessarily the same in all years, and no surveys were conducted in 1985 and 1991. Data from the Maine Atlantic Salmon Commission (ASC). Chart from KRIS Sheepscot V 1.0.

A map of Atlantic salmon redd counts in the Sheepscot River shows that fish do not run above Sheepscot Pond to spawn. The low gradient and lack of falls or other natural impediments to migration would have allowed historical salmon access to the headwaters of the watershed, including above Sheepscot Pond. Therefore, the current distribution of Atlantic salmon in the Sheepscot River is less than that historically used by the species. Data from the ASC and US Fish and Wildlife Service. Map from KRIS Sheepscot V 1.0.

A map of Atlantic salmon redd counts in the Sheepscot River shows that fish do not run above Sheepscot Pond to spawn. The low gradient and lack of falls or other natural impediments to migration would have allowed historical salmon access to the headwaters of the watershed, including above Sheepscot Pond. Therefore, the current distribution of Atlantic salmon in the Sheepscot River is less than that historically used by the species. Data from the ASC and US Fish and Wildlife Service. Map from KRIS Sheepscot V 1.0.

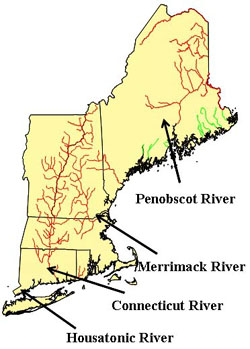

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries Division (USFWS/NOAA, 2000) found that Atlantic salmon in the Northeast United States had diminished considerably from their historic range. They also identified three DPS units: Long Island Sound, Central New England, and the Gulf of Maine DPS with the latter being the only population not extinct. USFWS (1999) also noted that:

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries Division (USFWS/NOAA, 2000) found that Atlantic salmon in the Northeast United States had diminished considerably from their historic range. They also identified three DPS units: Long Island Sound, Central New England, and the Gulf of Maine DPS with the latter being the only population not extinct. USFWS (1999) also noted that:

- "The Gulf of Maine DPS represents the remaining genetic legacy of a U.S. Atlantic salmon resource that formerly extended from the Housatonic River to the headwaters of the Aroostook River......

- The loss of these populations would restrict the natural range of Atlantic salmon to the region above the 45th parallel and beyond the borders of the United States."

The Sheepscot River Atlantic salmon population is not alone in showing recent declines. This chart, from Legault (2004), shows that the cumulative population in DPS rivers has dropped since 1995. Returns have trended downward with estimates ranging from the low hundreds to just a few dozen adults in 2002. Three rivers were thought to have no returns in 2002, while the combined estimated returns to the other four rivers were 23 to 46 adult salmon. (Kircheis, 2002). The decline after 1995 is one of the reasons that USFWS (1999) sought protection for the Gulf of Maine DPS under the ESA.

The Sheepscot River Atlantic salmon population is not alone in showing recent declines. This chart, from Legault (2004), shows that the cumulative population in DPS rivers has dropped since 1995. Returns have trended downward with estimates ranging from the low hundreds to just a few dozen adults in 2002. Three rivers were thought to have no returns in 2002, while the combined estimated returns to the other four rivers were 23 to 46 adult salmon. (Kircheis, 2002). The decline after 1995 is one of the reasons that USFWS (1999) sought protection for the Gulf of Maine DPS under the ESA.

Wild juvenile Atlantic salmon have been trapped from each of the Gulf of Maine DPS rivers and are being raised to adulthood and spawned at the Craig Brook National Fish Hatchery (at left). The fry and parr from this effort are then used to restock the rivers from which the captive broodstock was taken. The survival and growth of young salmon released to the wild is studied, and efforts are underway to restore habitat and improve water quality in a cooperative effort to prevent the extinction of Atlantic salmon in the Sheepscot River basin and other DPS rivers.

Wild juvenile Atlantic salmon have been trapped from each of the Gulf of Maine DPS rivers and are being raised to adulthood and spawned at the Craig Brook National Fish Hatchery (at left). The fry and parr from this effort are then used to restock the rivers from which the captive broodstock was taken. The survival and growth of young salmon released to the wild is studied, and efforts are underway to restore habitat and improve water quality in a cooperative effort to prevent the extinction of Atlantic salmon in the Sheepscot River basin and other DPS rivers.

Relationship to Other Hypotheses (Potential Casual Mechanisms)

Hypothesis #2: Elevated summer water temperature is identified as a factor limiting Atlantic salmon recovery in the Sheepscot River by this hypothesis and it is likely that it is one of the impediments to recovery.

Hypothesis #3: This hypothesis suggests that channel changes caused by sedimentation, lack of large wood and disturbed riparian conditions have changed habitat substnatially from conditions with which Atlantic salmon co-evolved and currently limit recovery of the species in the Sheepscot River.

Hypothesis #4: Dams are recognized as the major cause for historic declines of Atlantic salmon in New England, including the Sheepscot River.

Hypothesis #6: This hypothesis suggests that introduced species of fish are limiting Atlantic salmon recovery due to both competition and predation. Exotic species may have a competitive advantage because habitat changes as well.

Alternate Hypothesis: The observed change in the distribution and abundance of Atlantic salmon in the Sheepscot River is within the natural range of variability.

Ocean conditions and fishing are known to have caused variable ocean survival of Atlantic salmon in the North Atlantic with attendant cycles in their abundance. Factors such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) (Dickson and Turrell, 2000) may have a depressing effect on Atlantic salmon survival and when such conditions reverse and become more favorable, salmon population will rebound.

Monitoring Trends to Test the Hypotheses

To see if Atlantic salmon populations are, indeed, just in natural remission and will rebound in the future, fish surveys like spawner and redd counts, creel census, downstream migrant trapping and more widespread electrofishing should be conducted.

References

Atkins, Charles G. 1887. The river fisheries of Maine. The fisheries and fishing industries of the United States. Vol. 1, Sect. 5, pp. 673-728.

Baum, E. 1997. Maine Atlantic Salmon: A National Treasure. Hermon, ME:, Atlantic Salmon Unlimited. 224 p.

Chase, Fannie S. 1941. Wiscctsset in Pownalborough. The Southworth-Anthoesen Press of Portland Maine, Vol. XV, 639 pp.

Dickson, R.R., and W.R. Turrell. 2000. The NAO: The dominant atmospheric process affecting oceanic variability in home, middle and distant waters of European Atlantic salmon. Pp. 92-115 in the Ocean Life of Atlantic Salmon: Environmental and Biological Factors Influencing Survival, D.H. Mills (ed.). Maiden, MA: Fishing News Books.

Foye, R.E. 1967. Maine Rivers: the historical Sheepscot. Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game. 9(2): 8-11.

Halsted, M. 2002. The Sheepscot River, Atlantic Salmon and Dams: A Historical Reflection. SVCA, Alna, MA. 36 p.

Kircheis, F.W., 2001. Annual Report to the Maine Legislature Fish and Wildlife Committee for the period January through December 2001. Maine Atlantic Salmon Commission, August, Maine. 59 p. [1.4 Mb]

Kircheis, F.W., 2002 Annual Report to the Maine Legislature Fish and Wildlife Committee for the period January through December 2002. Maine Atlantic Salmon Commission, August, Maine. 73 p. [2.4 Mb.

Legault, C.M. 2004. A Population Viability Analysis Model for Atlantic Salmon in the Maine Distinct Population Segment. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Orono, ME. Reference Document 04-02. 98 p. [725kb]

Maine Atlantic Salmon Task Force (MASTF). 1997. Atlantic Salmon Conservation Plan for Seven Maine Rivers. Task Force appointed by the Governor of Maine. 353 p. [1.6Mb]

Meister, A.L. and R.E. Foye. 1963. Sheepscot River Drainage Fish Management and Restoration. Atlantic Sea Run salmon Commission and the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game. 35 p.

Meister., A.L. 1982. The Sheepscot River: An Atlantic Salmon River Management Report. Atlantic Sea Run Salmon Commission, Bangor, Maine. [3.7Mb]

National Research Council. 2002. Genetic status of Atlantic salmon in Maine: Interim Report. National Academy Presshis Washington, D.C.. http://www.nap.edu/books/0309083117/html/

National Research Council. 2003. Atlantic Salmon in Maine. Committee on Atlantic Salmon of Maine, National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy Press, Washington D.C. [3.5Mb]

Stickney, A. P., 1959. Untitled report summarizing Atlantic salmon research and findings on the Sheepscot River and estuary. Pages 6-17 in Progress in Sport Fishery Research, 1959. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Circular 81. Boothbay Harbor, ME. 13 pp. [125kb]**

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2000. Endangered and Threatened Species; Final Endangered Status for a Distinct Population Segment of Anadromous Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) in the Gulf of Maine. Federal Register Notice Vol. 65, No. 223 / Friday, November 17, 2000 / Rules and Regulations. Pages 69459-69483 [225 kb]